Join us: facebook.com/unitedhumanists

A Few Words About That Ten-Million-Dollar Serial Comma.

The case of the Maine milk-truck drivers who, for want of a comma, won an appeal against their employer, Oakhurst Dairy, regarding overtime pay (O’Connor v. Oakhurst Dairy) has warmed the hearts of punctuation enthusiasts everywhere, from the great dairy state of Wisconsin to the cheese haven of Holland.

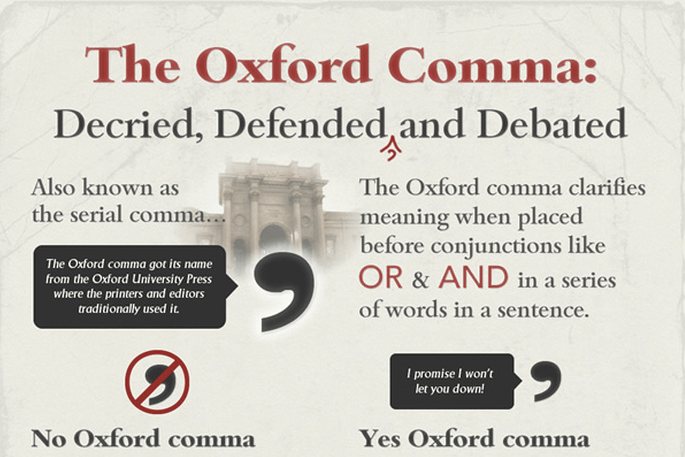

Nothing, but nothing—profanity, transgender pronouns, apostrophe abuse—excites the passion of grammar geeks more than the serial, or Oxford, comma. People love it or hate it, and they are equally ferocious on both sides of the debate. Individual publications have guidelines that sink deep into the psyches of editors and writers. The Times, like most newspapers, does without the serial comma. At The New Yorker, it is a copy editor’s duty to deploy the serial comma, along with lots of other lip-smacking bits of punctuation, as a bulwark against barbarianism.

While advocates of the serial comma are happy for the truck drivers’ victory, it was actually the lack of said comma that won the day. Here are the facts of the case, for those who may have been pinned under a semicolon. According to Maine state law, workers are not entitled to overtime pay for the following activities: “The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying, marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution of: (1) Agricultural produce; (2) Meat and fish products; and (3) Perishable foods.”

The issue is that, without a comma after “shipment,” the “packing for shipment or distribution” is a single activity. Truck drivers do not pack food, either for shipment or for distribution; they drive trucks and deliver it. Therefore, these exemptions do not apply to drivers, and Oakhurst Dairy owes them some ten million dollars.

Judge David J. Barron’s opinion in the case is a feast of subtle delights for anyone with a taste for grammar and usage. Lawyers for the defense conceded that the statement was ambiguous (the State of Maine specifically instructs drafters of legal statutes not to use the serial comma) but argued that it had “a latent clarity.” The truck drivers, for their part, pointed out that, in addition to the missing comma, the law as written flouts “the parallel usage convention.” “Distribution” is a noun, and syntactically it belongs with “shipment,” also a noun, as an object of the preposition “for.” To make the statute read the way the defendant claims it was intended to be read, the writers would have had to use “distributing,” a gerund—a verb that has been twisted into a noun—which would make it parallel with the other items in the series: “canning, processing,” etc. To the defendant’s contention that the series, in order to support the drivers’ reading, would have to contain a conjunction—“and”—before “packing,” the drivers, citing Antonin Scalia and Bryan Garner, said that the missing “and” was an instance of the rhetorical device called “asyndeton,” defined as “the omission or absence of a conjunction between parts of a sentence.”

Lest we lose perspective, this law on the books of the State of Maine applies to people who work with perishable foods, and the point is that pokey employees should not be rewarded for taking their sweet time getting the goods to market. Possibly (but improbably) for this reason, in an effort to illustrate (or not) ambiguity in a series, the coverage of O’Connor v. Oakhurst Dairy served up a lot of food imagery. The Times noted that it would break with style and add the serial comma in the following sentence: “Choices for breakfast included oatmeal, muffins, and bacon and eggs.” The Guardian, too, would avoid ambiguity at the breakfast table: “He ate cereal, kippers, bacon, eggs, toast and marmalade, and tea.”

Contrast these with a dinner described in a recent e-mail from John Pope, the author of a collection of obituaries that ran in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, who remains adamant in his rejection of the serial comma: “The next day, I enjoyed pan-roasted oysters with a tomato sauce over rice, broccoli salad and bread pudding with chocolate sauce.” A comma after “broccoli salad” would have cleared the table before dessert.

The case of the dairy-truck drivers’ comma has got several things going for it. It’s got David and Goliath in the story of the little guy sticking it to a corporate boss. It’s got men driving around in trucks with copies of Strunk & White in the glove compartment. And you know what else it’s got? Of course you do. It’s got milk. For all the backlash against the dairy industry—the ascendance of soy milk, almond milk, hemp milk (note the asyndeton), none of which, by the way, are really milk, because you can’t milk a hazelnut—there is something imperishably wholesome about cows and milk.

Got milk? Got commas?

Source: https://bit.ly/3gEtQWG